Most people are familiar with common literary devices such as similes, metaphors and alliteration.

Most people are familiar with common literary devices such as similes, metaphors and alliteration.

Yet there are numerous other devices that are frequently used – both in literature and in everyday speech – without getting the recognition they deserve.

What exactly are literary devices?

According to Literary Devices, the term commonly refers to the typical structures used by writers to convey their message(s) in a simple manner to their readers. When employed properly, different literary devices help readers to appreciate, interpret and analyse a literary work.

There are two types of literary devices: literary elements (such as plot, setting and dialogue) and literary techniques. This blog post concerns the latter category.

A few lesser-known literary devices

Let’s delve into three different figures of speech that you probably use in daily life, without realising they had a name!

Litotes

Litotes derives from an ancient Greek word meaning ‘simple’ and is basically the opposite of hyperbole. It’s defined by the OED as “an ironical understatement in which an affirmative is expressed by the negative of its contrary”.

To put this in plain English, litotes often takes the form of a double negative, e.g. a positive statement such as “it’s good” is transformed into “it’s bad” and then negated – resulting in “it’s not bad”. Another example is saying, “She’s no spring chicken” as an alternative to saying “She’s old”.

The Guardian describes litotes as “the most common rhetorical device you’ve never heard of”. Loved by politicians in particular, it’s best appreciated as a kind of rhetorical magician or illusionist – deliberately drawing our attention to something while simultaneously emphasising its opposite.

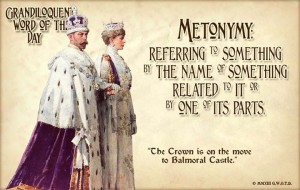

Metonymy

The word metonymy comes from the Greek metōnymía, literally ‘a change of name’. It’s a figure of speech in which an object or concept is called not by its own name but by the name of something of which it’s an attribute or with which it’s closely associated.

The word metonymy comes from the Greek metōnymía, literally ‘a change of name’. It’s a figure of speech in which an object or concept is called not by its own name but by the name of something of which it’s an attribute or with which it’s closely associated.

Using a metonymy serves a dual purpose: it breaks up any repetition of the same phrase and it makes the sentence more interesting by changing the wording.

One of the most famous examples is the saying, “The pen is mightier than the sword”. In fact, this comprises two metonymies, with the “pen” standing in for “the written word” and the “sword” standing in for “military aggression and force”.

Other examples of metonymy include: use of “the Crown” in place of the word “king” or “queen”, “Hollywood” for “the US film industry” or “Downing Street” for “the UK Government”.

Synecdoche

Synecdoche, from Greek synekdoche, meaning ‘simultaneous understanding’, is a sort of poetic shorthand used by writers to achieve brevity and add colour to their words. It’s defined by Merriam-Webster as “a figure of speech by which a part is put for the whole, the whole for a part, the species for the genus, the genus for the species, or the name of the material for the thing made”.

Synecdoche often refers to the whole of a thing by the name of any one of its parts. Some examples include calling a car “wheels”, business executives “suits” or coins “coppers”. Other examples are “taking her hand in marriage” when it is in fact the whole person who’s betrothed, or saying “Italy won the World Cup” instead of specifying that it was actually won by “the Italian football team”.

Synecdoche and metonymy are easily confused. The tip to remember is that synecdoche is a subclass of metonymy; however, not all metonymies are synecdoche as the word used isn’t necessarily a part of it – it can just be related to it.

Over to you

Which of these literary devices had you heard of before and which were new to you? Any others that you think should belong here? If so, please share in the comments.

Thank you, fascinating. I’ve printed them off for my high school children who have to use technical analysis in their essays. Never know, they might get a few extra marks for these lesser known literary devices!

Thanks for your comment. So glad you found it interesting and hopefully it’ll be of some use to the kids!